Background

At the end of 2023, I moved to the Häggvik district in Sollentuna municipality in northern Stockholm (Sweden). That Sollentuna municipality was a central place during the Iron Age is evident from all the runestones and hundreds of burial grounds that have been found in the area. Even today, Sollentuna’s municipal coat of arms is an illustration of three vikingships standing on logs. Because where Sollentuna is now located, a thousand years ago there was a waterway where ships were rolled on logs from Saltsjön via Norrviken and Edsviken on their way to Uppsala. A trading post called Tuna arose there. Unfortunately, many archaeological monuments are now destroyed by road construction and house building, but this also means that large parts of the area have been archaeologically excavated in connection with these constructions.

As a reenactor and history nerd, I sat one evening aimlessly browsing the Historical Museum’s database of finds from the area and found a fantastically well-preserved belt from the late Viking Age and when I checked the location of the find, it turned out to come from an excavated grave about 200 m from my front door. My reenactment heart skipped a beat and I felt I had to try to recreate this grave. As usual, the project quickly grew to unreasonable proportions and I decided to try to recreate clothes and grave goods from TWO buried Sollentuna residents from the Viking Age. A man and a woman who lived here during the 11th century. Graves A11 and A28.

I started by looking at maps in the National Heritage Board’s app “Fornsök” and of course walking to the discovery site. Today it is a parkarea over a motorway tunnel. The archaeological excavation was done in 1994-1995 so it is about 30 years since the graves were excavated and already then most of them were damaged by, among other things, earthen cellars. The grave field is located just north of the place where the former “Skälby By” was located and part of the village road ran the same distance as the footpath I walk to the commuter train.

I also scoured the internet for all the information I could find about the excavation and borrowed the National Heritage Board’s excavationreport from the Vitterhetsakademin library. It turned out to be a very detailed and exciting read, 200 pages long with maps, tables of findings and interpretations compiled by Gunnar Andersson. A goldmine for a nerd.

The burial field contained 45 graves, of which about half were cremation graves and half were skeleton graves. The grave with the belt is a skeleton grave named A11. After reviewing all the graves in the report, I decided to also try to recreate the women’s grave A28 as it is dated to the same time period and contained exciting finds. It is even likely that these two people knew each other a thousand years ago.

As an reenactor and archaeology enthusiast, it is exciting to dig into (pun intended) a project about 11th century Uppland as it is a place in the middle of a religious and cultural shift where old and new traditions meet.

General information about the grave field

Of the 42 graves in total, all but two can be dated to the Viking Age, around 900-1100 AD. The last two graves date to the pre-Roman Iron Age, around 300 BC. Christian skeleton graves lie side by side with cremation graves from the same period. Religious beliefs probably played less of a role than family lineage and affiliation to the geographical location.

Under the graves were found remains of houses from the Migration Period (approx. 350-550 AD) and above the graves were traces of forges belonging to Skälby village which are C14 dated to 1400-1600 AD. In other words, people have been working here for a long time.

In the Viking Age, child mortality was high. About 30% of the individuals in the grave field are 0-10 years old. A 6-8 year old was buried with over 70 small glasbeads. This child must have come from a wealthy family and been deeply mourned.

The finds at the grave site also show extensive contacts abroad. Beads from the Middle East and Asia, silk and belt fittings from the Orient. Among the grave finds are also arab silver coins from the 9th century and a German silver coin from 1056.

The graves contained bones from horses, dogs, cats, chickens, pigs, squirrels and cattle. The most common animal bones was from dogs. Ceramics were found in the cremation graves used as burial urns. Many composite bone combs were found. Thor’s hammer rings were found in ten of the graves. Also in several of the Christian-interpreted skeleton graves.

The graves also had bronze needle cases, keys, fire steel and many knives but no tortoise brooches or fibulaes, probably because the fashion for apron dresses with double brooches had gone out of fashion in Uppland in the 11th century.

What can the archaeological report tell us about the man in A11 and the women in A28?

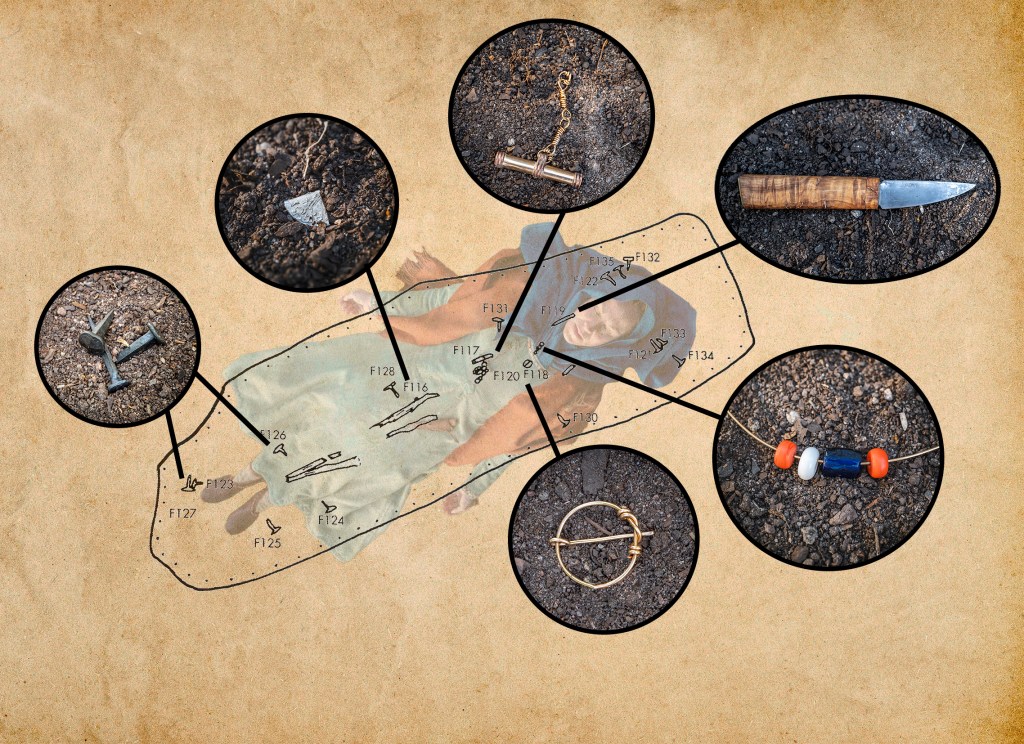

Grave A11

The grave was covered with a round pile of stones and was located on the crest of a hill. A burial place for someone important. He was buried in a 2.2m long wooden coffin with 19 coffin nails, which indicates a Christian burial.

In the grave was a preserved skull, cervical vertebrae, shoulder and thigh and shin bones of a male individual who was about 25-35 years old. The C14 dating says that he died in 1060 plus or minus 40 years.

At thigh height lay the belt with bronze fittings. There was also a whetstone, the remains of an iron knife with a wooden handle and fragments of a possible sweepbox/wooden bowl with twisted silver wire.

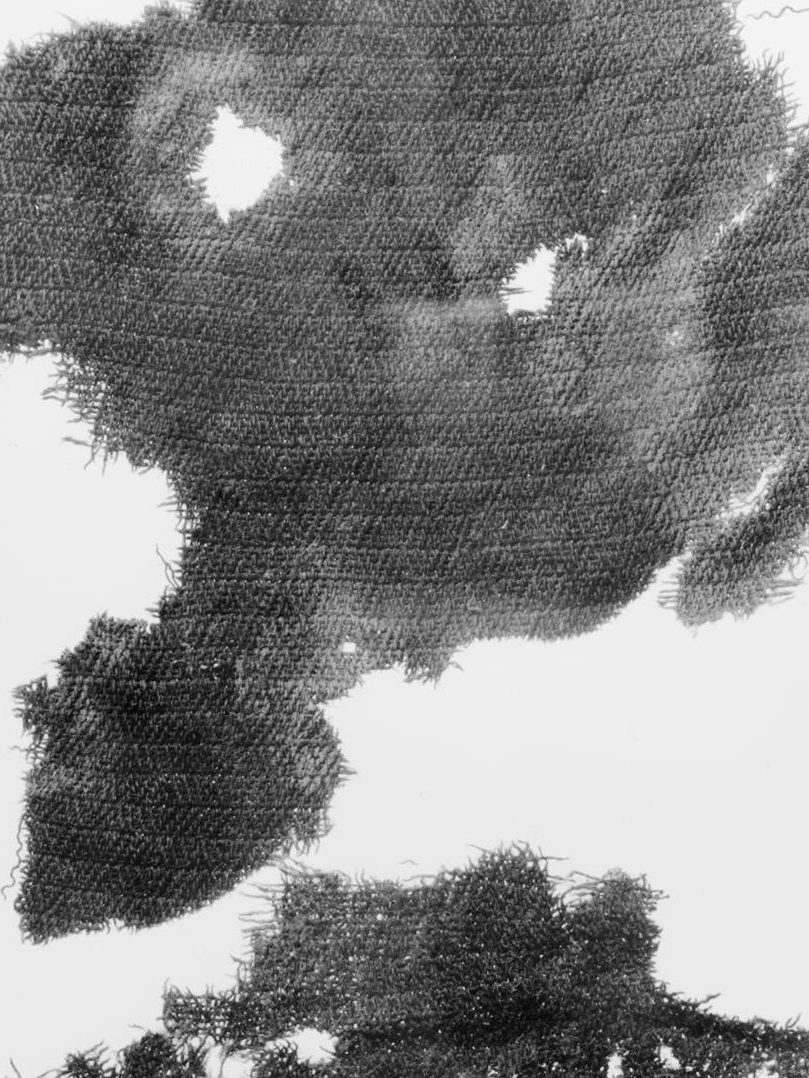

But the most exciting thing is that Andersson writes that “on the back of the belt were fragments of a linen fabric, woven in plain weave with Z-sun thread, and on the belt’s buckle were fragments of a woolen fabric.” As a textile nerd, I am a little extra happy about that find.

Grave A28

A28 was also a skeleton grave but with significantly worse preserved bone material and the osteological examination says that it was a woman who was about 35-64 years old.

In the grave was a German silver coin dated to the year 1056. The coin was located at the right femur, probably placed on the deceased.

The grave was damaged so it probably contained more grave goods from the beginning but what remained were two red opaque glass beads, a white opaque glass bead and a blue faceted glass bead. She also had a bronze needle case in the same model as found at Birka, among other places.

In the grave was also a small ring buckle and the remains of a knife with preserved silk threads next to the blade. (The textile nerd in me got excited about that find.)

Based on the grave goods left in the damaged grave, not least the silk, I interpret it as the woman in A28, like the man in A11, belonged to a family of relatively high social status. This is important for the choice of fabric qualities and colors in my attempt to recreate the clothing of these two buried individuals.

Were they perhaps friends of Estrid Sigfastdotter?

Only a two-hour walk from the graves in Häggvik is the village Broby, where Estrid Sigfastdotter lived around 1020-1080. She is one of Sweden’s oldest skeletal finds that has been identified by name thanks to several runestones in the area and a written source from her pilgrimage to a monastery in southern Germany. Estrid belonged to the power elite, her father Sigfast was one of king Olof Skötkonung’s closest men and her first husband Östen died on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Estrid had many children and also outlived her second husband Ingvar. She was therefore a very influential and Christian celebrity in the 11th century and it is likely that the woman in grave A28 and the man in grave A11 knew Estrid and her family. At least they were part of the same social class in the same geographical area during the same time period and were buried as Christians. It is an exciting thought.

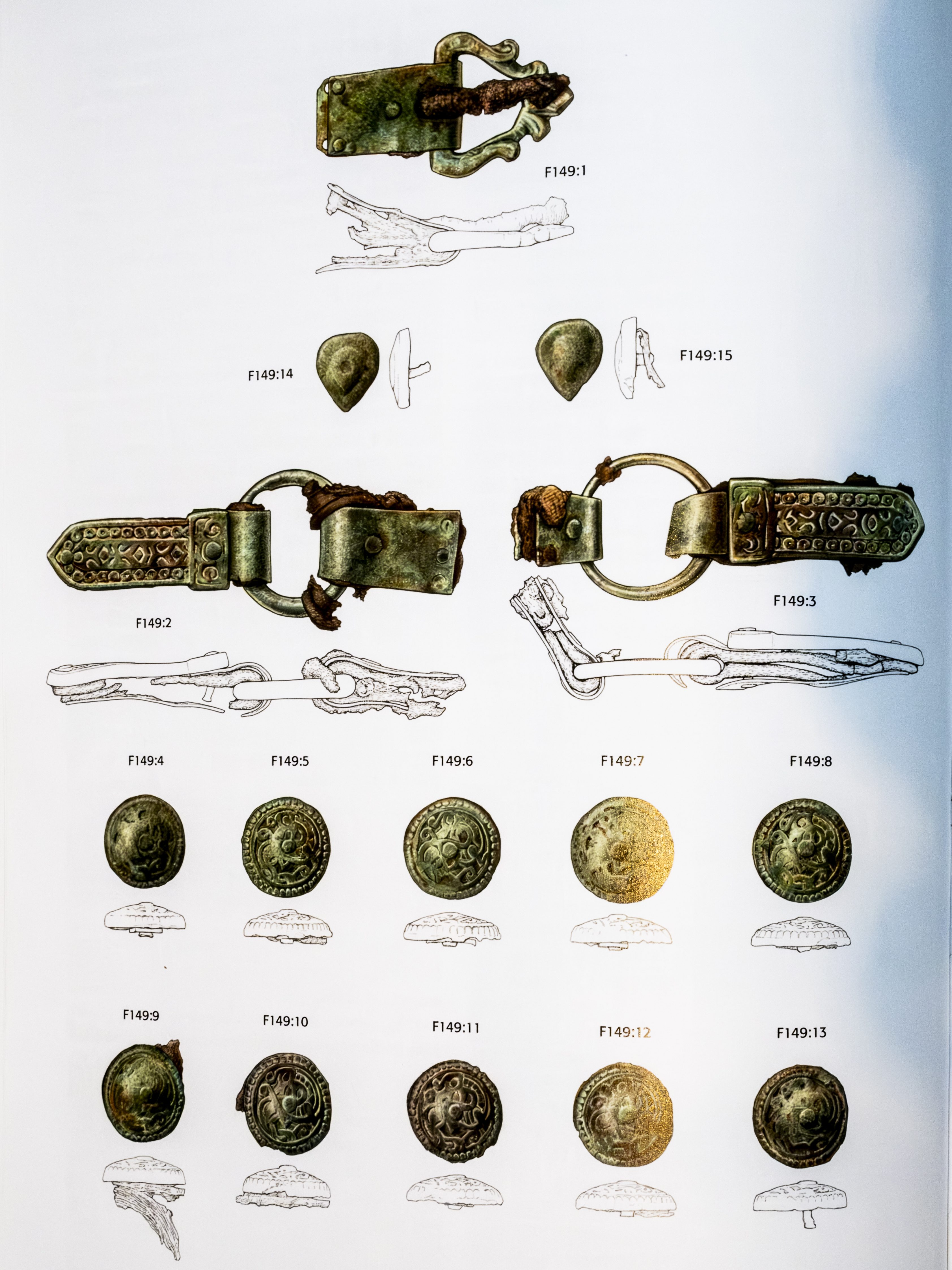

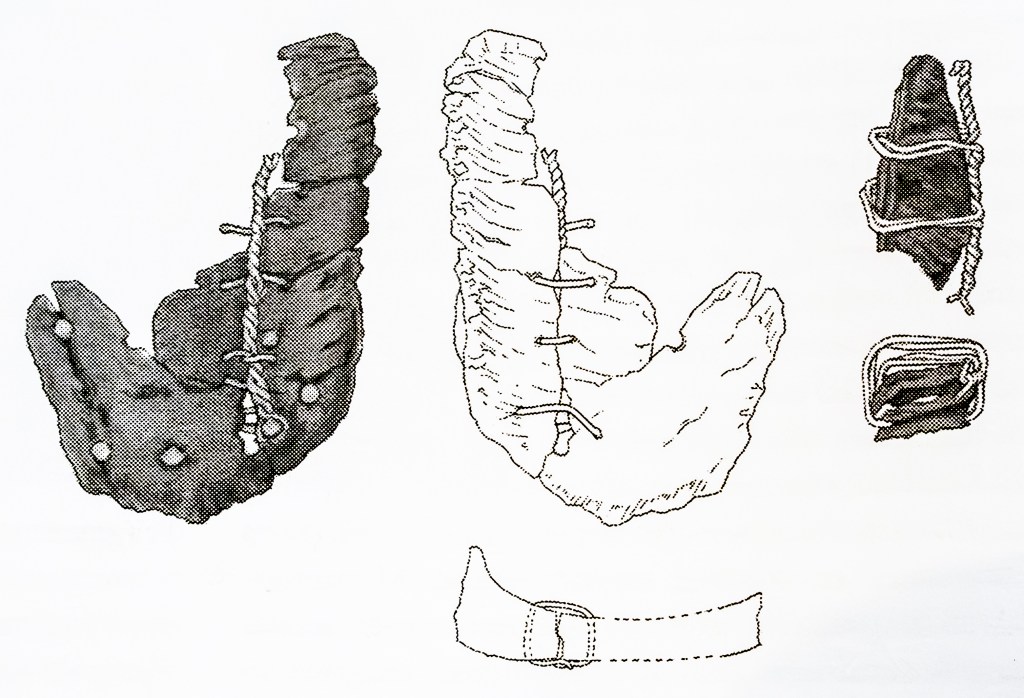

The man belt

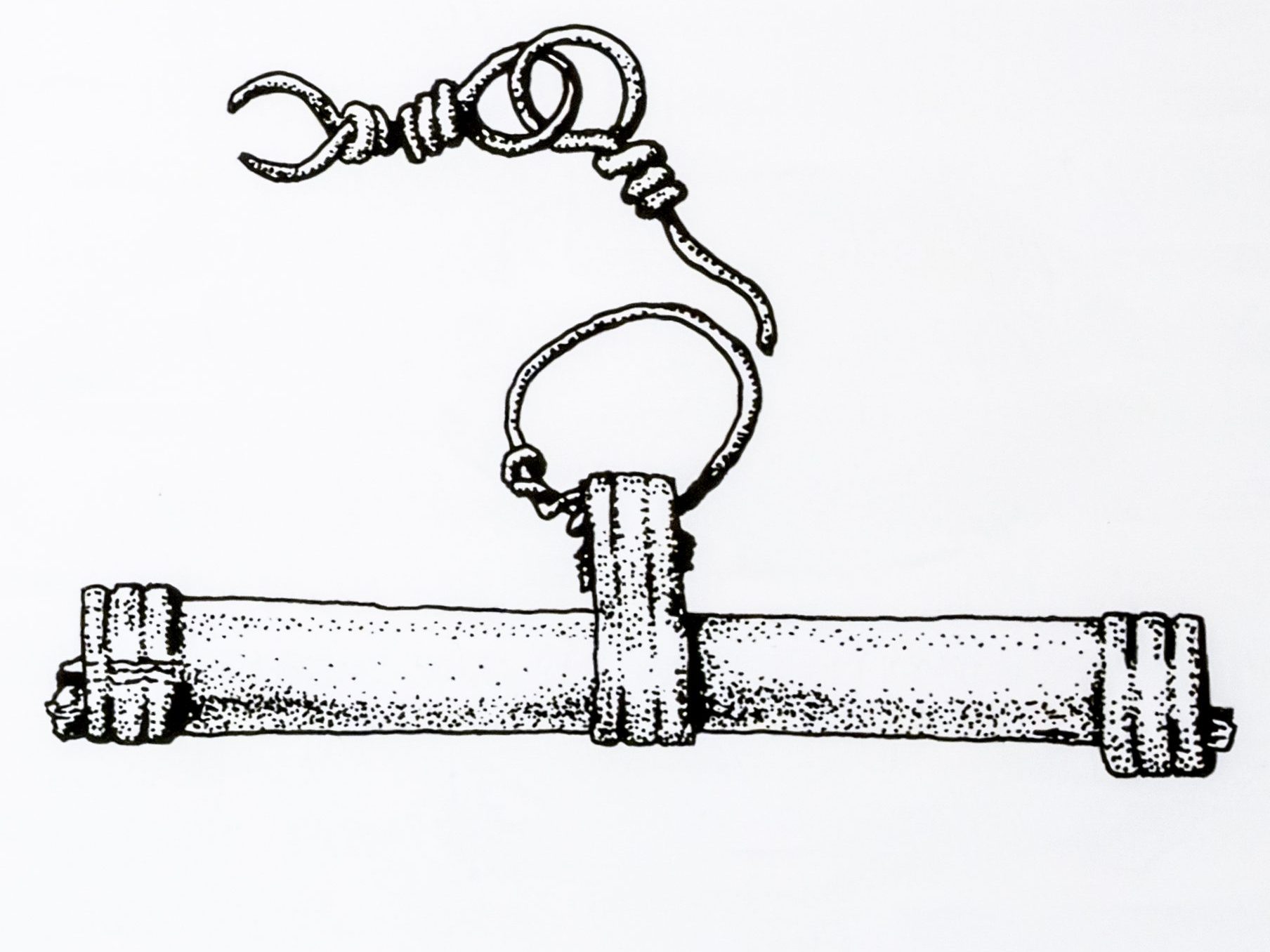

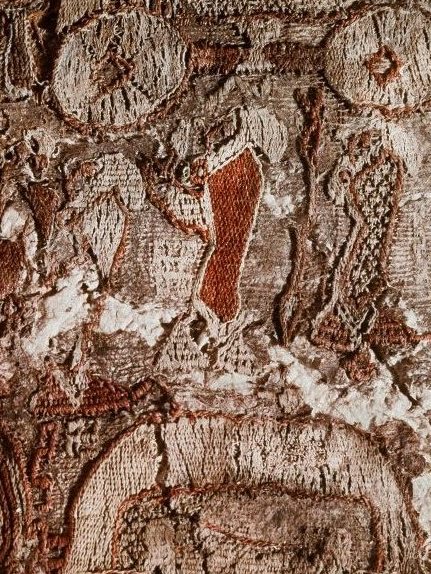

The belt in grave A11 is truly magnificent with 10 round fittings, 2 heart-shaped fittings, two interconnected strap fittings with bearing rings and a buckle in bronze/copper alloy.

.

The round fittings have Nordic animal ornaments, the strap fittings and the buckle plant ornaments and the two heart-shaped ones are typically Eastern fittings, probably made in the Orient.

There is much evidence to suggest that some belts in the Viking Age were made of thin, folded and sewn leather rather than the thick cut belts we see today. If I understand correctly, it was difficult to tan thick leather. The belts were also short, adapted to the person who would wear them. And the belts were worn at navel height, not further down.

It was incredibly exciting to take a closer look and photograph the original objects at the Historical Museum and discover how well preserved the leather is between the bronze plates. You can clearly see the width of the belt and I believe the leather is thin and folded. In the archaeological report the leather belt is described as about 2 cm wide which matches the dimensions of the fittings. Thank you Maria Neijman for a very nice visit to the museum’s collections.

I also see something that could be holes from stitching in the leather but it is difficult to determine without opening the plates which of course I cannot do. In other words, the belt could be made of a cut thicker leather but it is more likely that it is a folded, sewn belt in thin leather. I chose to use a vegetable tanned leather, about 1.2 mm thick. After cutting, I soaked the leather, folded the edges towards the middle, fixed with leather glue and let it dry under pressure. I wanted to avoid a center seam on the back because it would get in the way of all the rivets and fittings. Then I stitched hundreds of small holes and sewed the edges with waxed linen thread. It was a time-consuming job but the result is a thin, strong and flexible belt.

All the bronze details for the belt are cast by @MagyarTarsoly based on the pictures I sent him of the original items. I am very happy with both the result and the delivery time

Then came the challenge of joining all the parts of the belt and hammering all the rivets. It was harder than I thought to hammer the rivets neatly and evenly, but with a good ball-point hammer the end result was ok. Thanks to Karl Kronlund for the advice and support.

The design and dimensions of the different parts of the belt are my interpretation based on the pictures and description in the archaeological report but also based on the measurements of my partner who will wear the belt.

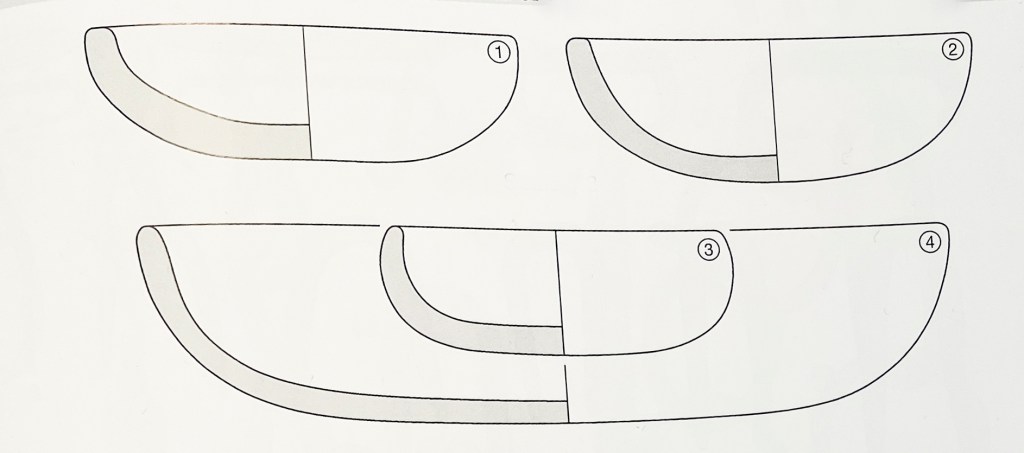

The knives

Both grave A11 and A28 contained a knife. Trying to recreate these two knives was both fun and challenging. Both were in poor condition when I looked at them in the Historical Museum’s archives, but the knife in A11 is described and drawn with wooden remains from the handle, and the knife in A28 had most of the tang remaining even though it had broken off. Both knives were around 9-12 cm long.

After looking at the originals, I enlisted the help of my friend Peter Johnsson and discussed the likely shape of the knife blade, edge and handle based on what were common shapes during the Scandinavian Viking Age. Below is a schematic diagram showing how the back of the knife blade is straight but dips slightly downwards towards the tip and how the entire edge is triangular shaped. The handle should be slightly flat at the top and oval-rounded at the bottom to fit comfortably in the hand. Although no remains of handle rivets have been found, I chose to join my knife handle and blade with brass rivets and a small brass plate.

I forged the knife blades with fantastic help from Thomas Cederroth in his forge on Skeppsholmen in Stockholm. I really enjoy being in a forge and forging is a wonderful craft. The smells, the glow of the fire and the material that magically changes form. It is peaceful and challenging at the same time.

Once home I started working on the handles and it was easier said than done. I managed to crack two nice pieces of wood before I got it right. Because of my failures I ran out of material and had to tinker a bit but in the end I was still satisfied. One knife has a handle of birch root and elk antler. The other has a handle of what I thought was birch root but when I rubbed some oil on the wood it changed color and I think it may be rowan. Finally my friend Faravid sewed two nice leather sheaths for the knives in hand-tanned leather.

The mans whetstone

If you have a knife, you also need a whetstone to keep your edges sharp. In grave A11 there was a very well-used whetstone, about 6 cm long. When I looked closer at it in the Historical Museum’s collection, my interpretation was that it had broken and had originally been longer. Whetstones are a common archaeological find from the Viking Age and are often 7-10 cm long with a drilled hole that makes it possible to hang it on your belt. That’s why I chose to buy a whetstone with a drilled hole, 8 cm long in slate.

The mans under tunic

In the archaeological report, Andersson writes that “on the back of one of the belt straps there were fragments of a linen fabric, woven in plain weave with Z-sunn thread. Andersson further writes that the linen could be fragments of trousers/hose, but I see it as more likely that it is an under tunic that the strap strap had been laying against where a woolen over tunic had slipped up. Unfortunately, the textile fragment is not preserved to be looked at more closely today. My interpretation could of course be wrong, but if you look at grave material from the Viking Age and art such as the Oseberg Tapestry, trousers/hose seem to be mostly made of wool that can be plantdyed, and linen trousers do not seem to occur to the same extent. Furthermore, my interpretation is that a man who was wealthy enough to wear a rich belt would also have a comfortable and washable linen tunic closest to his body. I therefore chose to interpret the linen fragment as a tunic and sew it in undyed linen plain weave. The model is straight, rectangular pieces with wedges.

The mans over tunic

The lack of fabric fragments in grave A11 means that the over tunic is also an interpretation from several different archaeological finds and depictions from Viking Age Scandinavia. Regarding the choice of material, I have assumed that the man comes from the upper class of society and should therefore be buried with a woolen tunic in strong colors and fine quality. So I have chosen to hand-sewn the tunic in a tightly woven plain weave, and then plant-dyed it with indigo. People probably plant-dyed blue with vejde in Scandinavia in the 11th century, but there may have been imported indigo and both plants have the same active ingredient. Finally, I have decorated the tunic with narrow strips of a silk that is a reconstruction of a Byzantine silk from the 10th century. The model is thigh-length and has two gussets in the sides. I base my interpretation on several different finds dated to the beginning of the 11th century, mainly from Denmark.

(National Museum of Denmark)

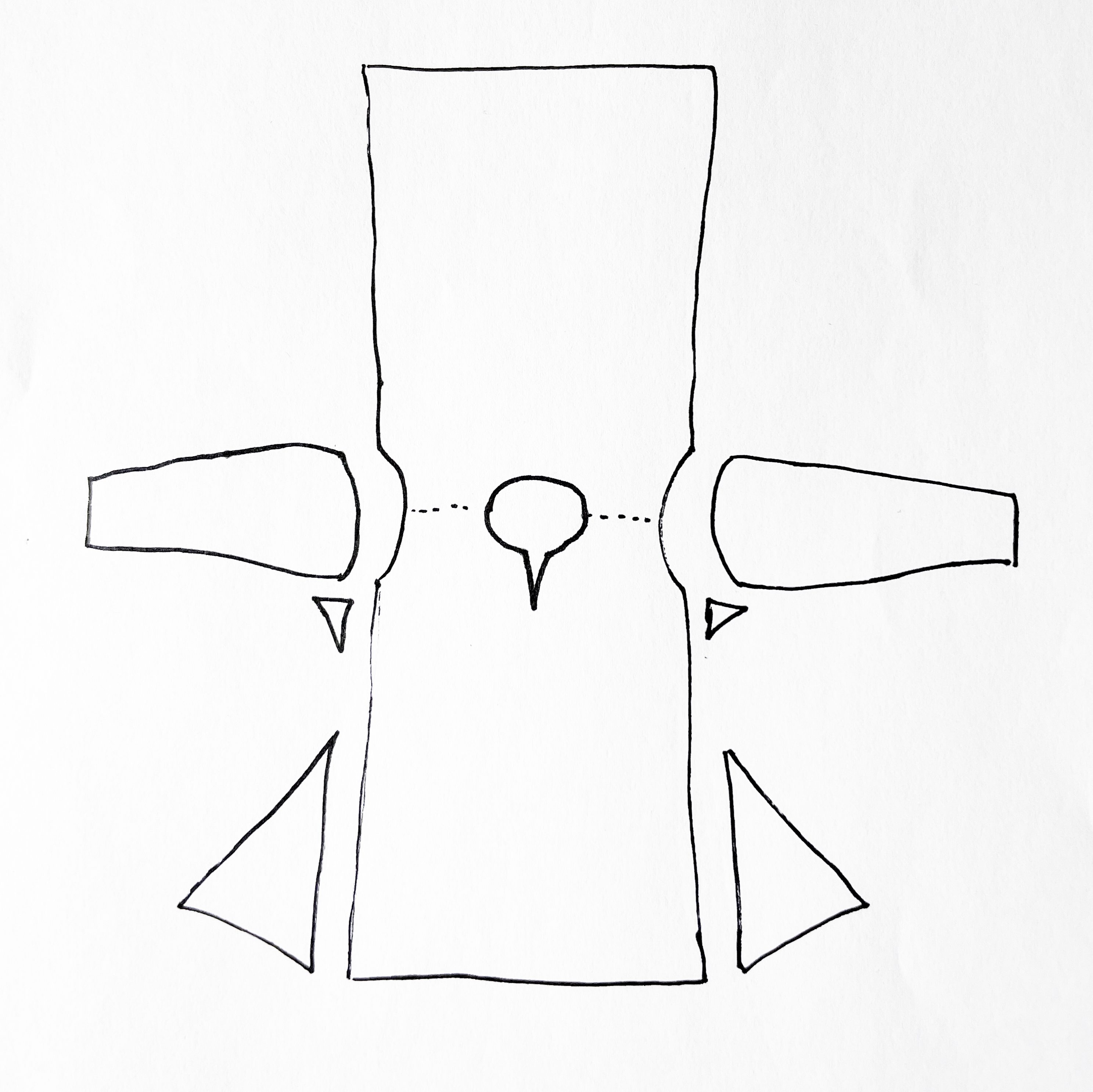

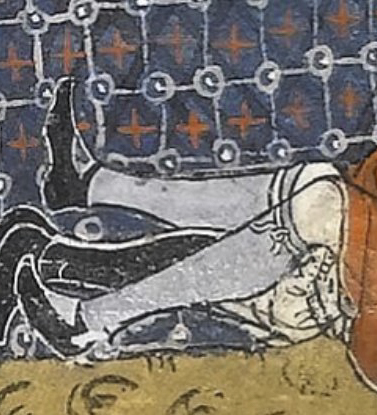

The mans trousers

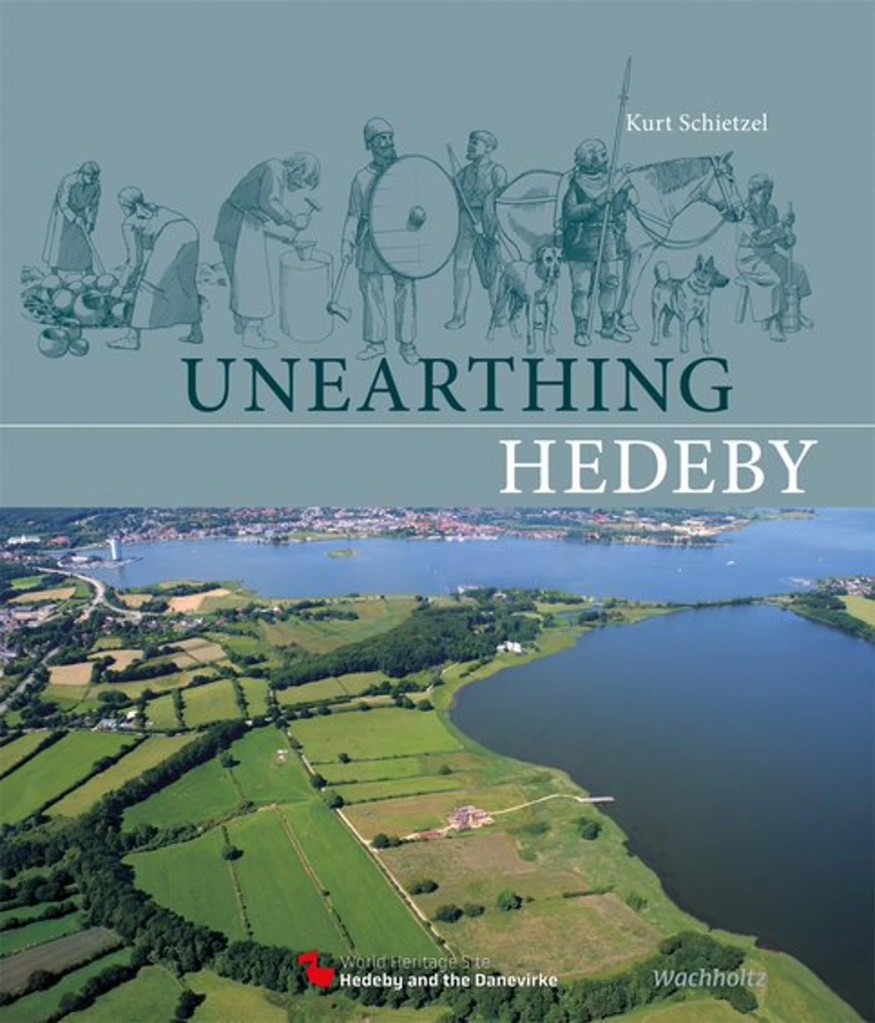

There were no remains of anything that I can interpret as trousers in grave A11 but I find it hard to believe that a rich, Viking Age man would be buried without legwear so I have had to base my interpretations on geographically more distant finds. I have chosen to base the trousers on a well-preserved archaeological find of trousers in wool from the Thorsbjerg bog which is today located in northern Germany but during the Viking Age was Danish territory. The find is dated to around the 5th century, that is, before the Viking Age but small fragments of similar trousers have also been found in Hedeby from the Viking Age.

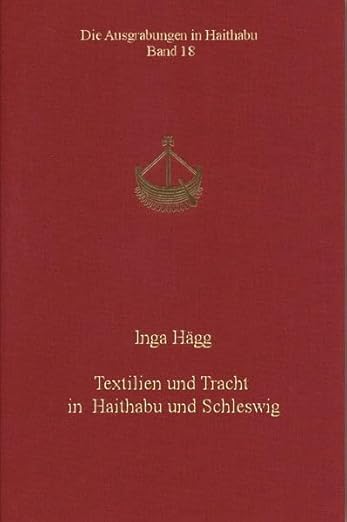

Depictions from the Viking Age indicate that there were both very wide, pleated trousers (so-called baggy trousers), hose with breeches and straight trousers in this model both with and without feet. For the time period of grave A11, I should choose hose and breeches. However, since my partner doesn’t like wearing hose and I think it’s an exciting challenge to sew a pair of Thorsbjerg trousers with a good fit, I choose that. I hand-sewn the trousers in undyed 2/2 wool twill and then dyed them light brown with walnut shells. The find in Thorsbjerg was mostly sewn in diamond twill, but several different fabric qualities were present and, according to Inga Hägg, they were dyed brown with walnut shells.

I chose to sew the trousers without a foot as it makes the construction easier, which was tricky to put together anyway. The find has seams that twist from the back along the legs to the front, creating a very tight fit. My trousers turned out really tight, but the construction, together with the elasticity of the 2/2 twill, means that they are surprisingly easy to move in. You can squat and probably ride in them. The fabric quality matches quite well with most textile finds from the city layers in Sigtuna from the beginning of the 11th century. Since the original has loops for a belt, I chose to weave a simple, narrow belt with sun-bleached linen thread with a small bronze buckle. All of these are interpretations are based on the very few archaeological finds we have of Viking Age trousers in Scandinavia, and I wish I had more and better sources to base my work on.

The mans legwraps

In several images from the Vendel and Viking eras, both in European art and on gold figures, you can see that many men have cloth wrapped over their trousers/hose from the knee down to the foot. The legwraps may have had many functions, protection against cold and sharp vegetation, abrasion protection when riding and like many other things, it probably became a fashion statement.

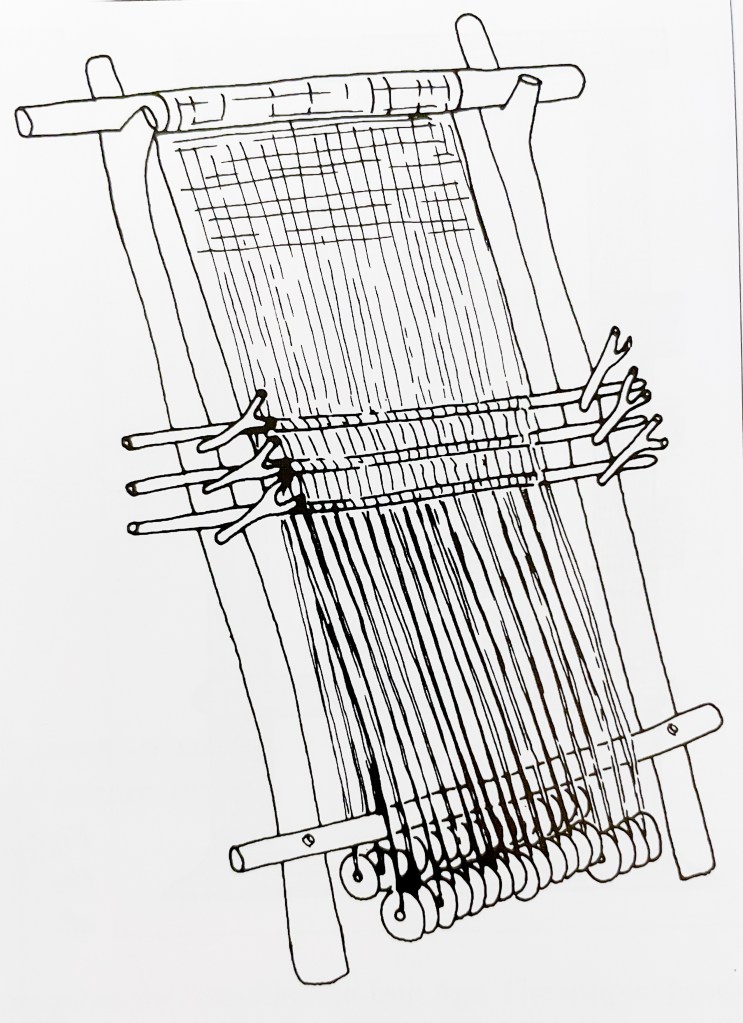

In Hedeby, archaeologists have found about five fabric fragments that have been interpreted as legwraps and Inga Hägg writes in “Textilfunde aus dem Hafen von Haithabu” that all the wool fragments are woven in herringbone twill. They are not sewn but woven as long wraps, about 10 cm wide. The weave is very dense and sturdy, that is, not very stretchy. With the help of Amica Sundström, I wove 8 meters of leg wraps based on the archaeological fragments. The weave is very thread-tight with 24 threads per cm in the warp and the legwraps became 11 cm wide. Then I plantdyed them blue with an extra strong vejde.

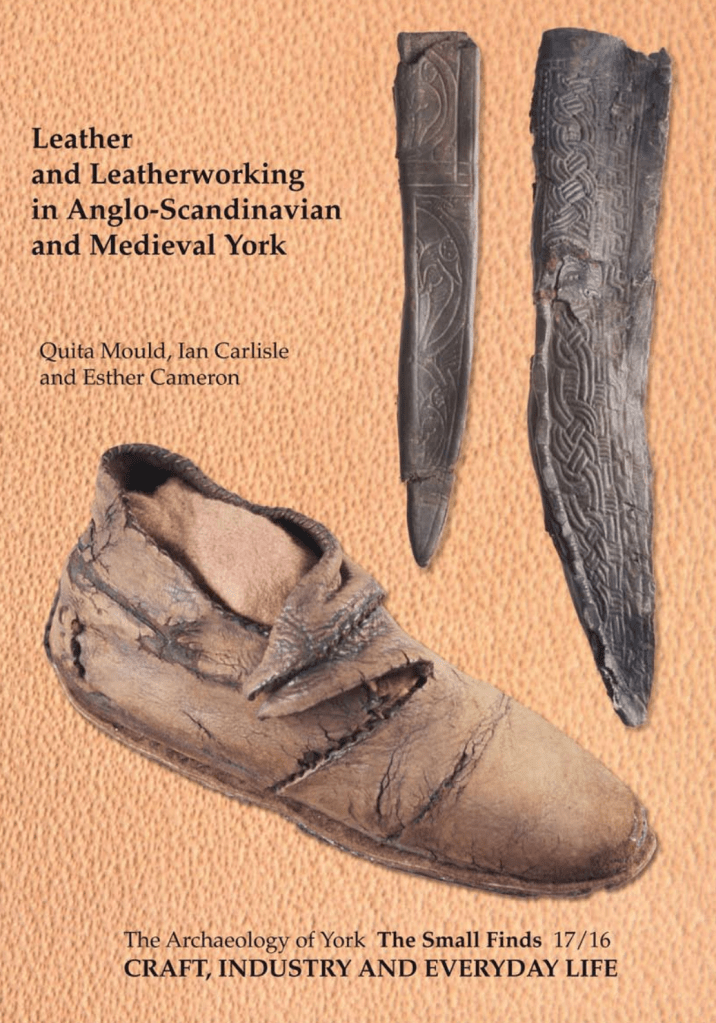

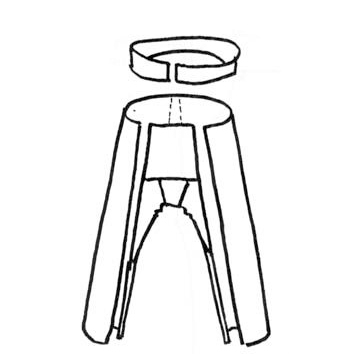

The mans shoes

No fragments of shoes were found in grave A11, but since leather decays quickly, it is extremely unusual to find preserved remains of shoes in graves from the Iron Age. However, I believe that people were buried with shoes because they took so many other grave goods and fancy clothes to the afterlife. And even though this is probably a Christian grave, the tradition of rich grave goods/personal belongings still lived on.

Since there are few Viking Age finds of shoes in Uppland, I chose to search geographically further away and looked at shoes found in Hedeby, Denmark. The choice fell on “Hedeby model number 6” in vegetable tanned leather, turned sewn by hand by Torvald.

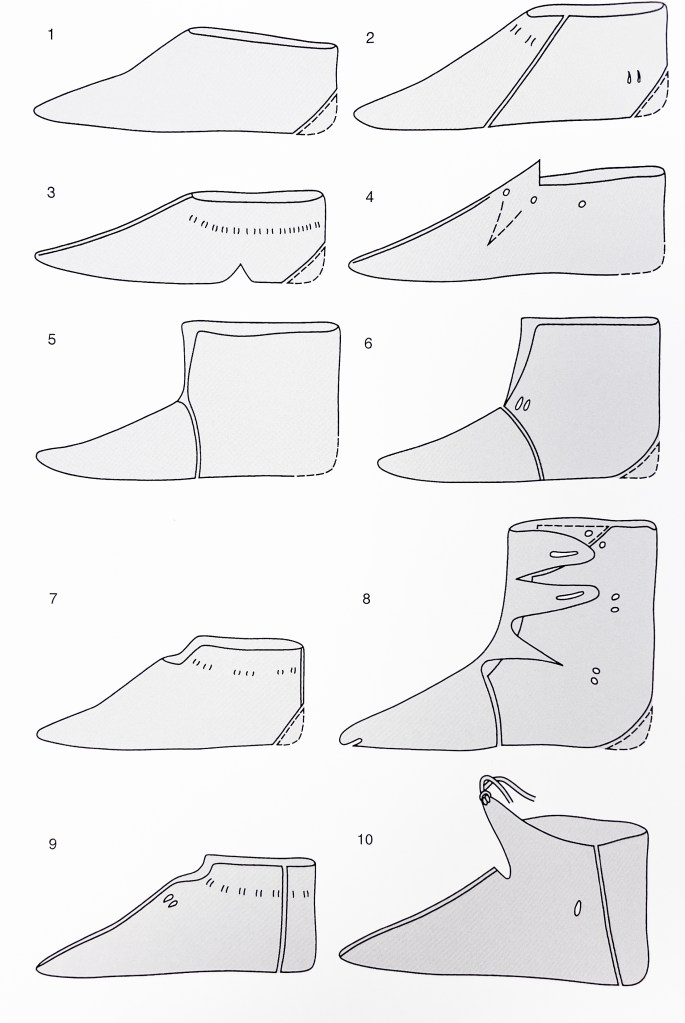

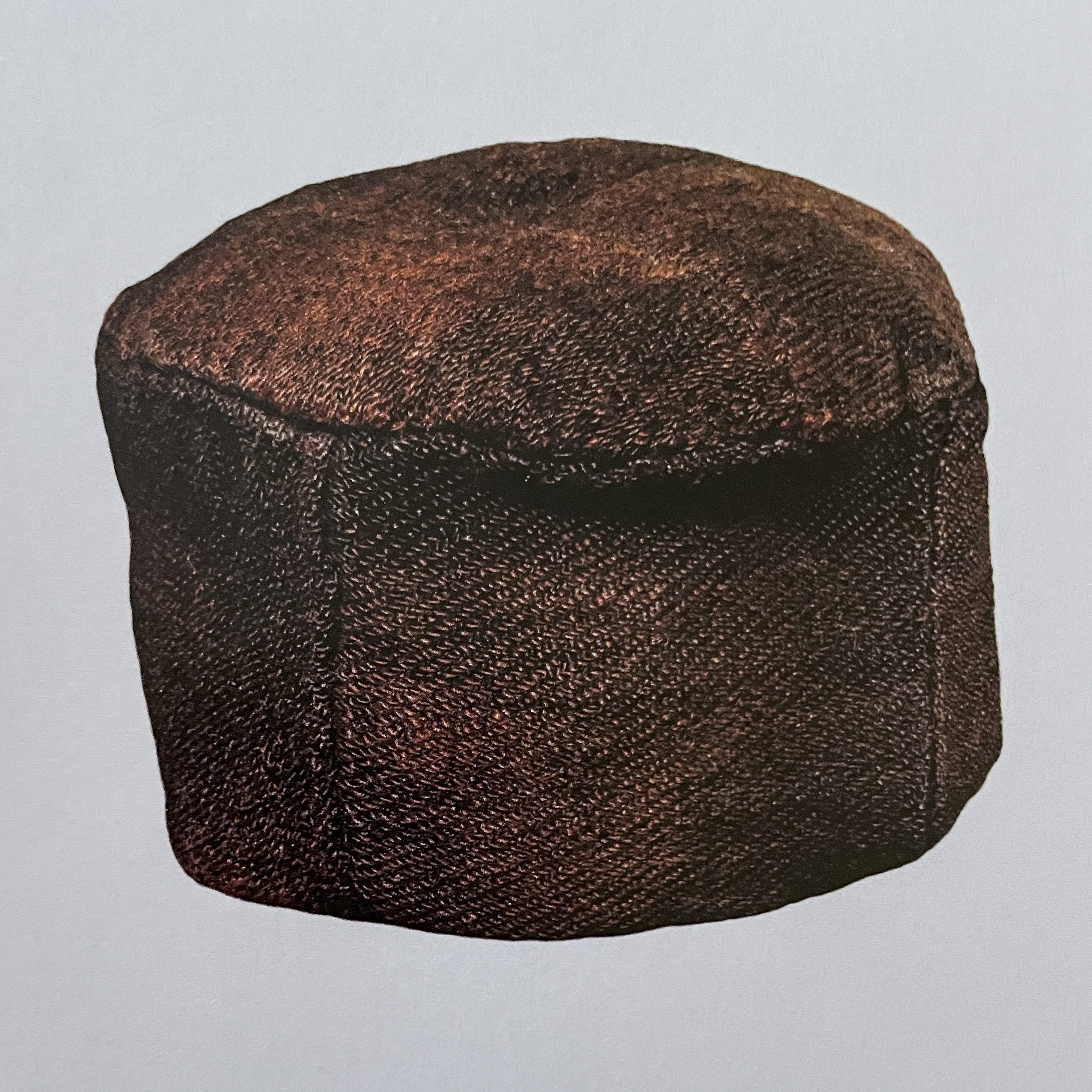

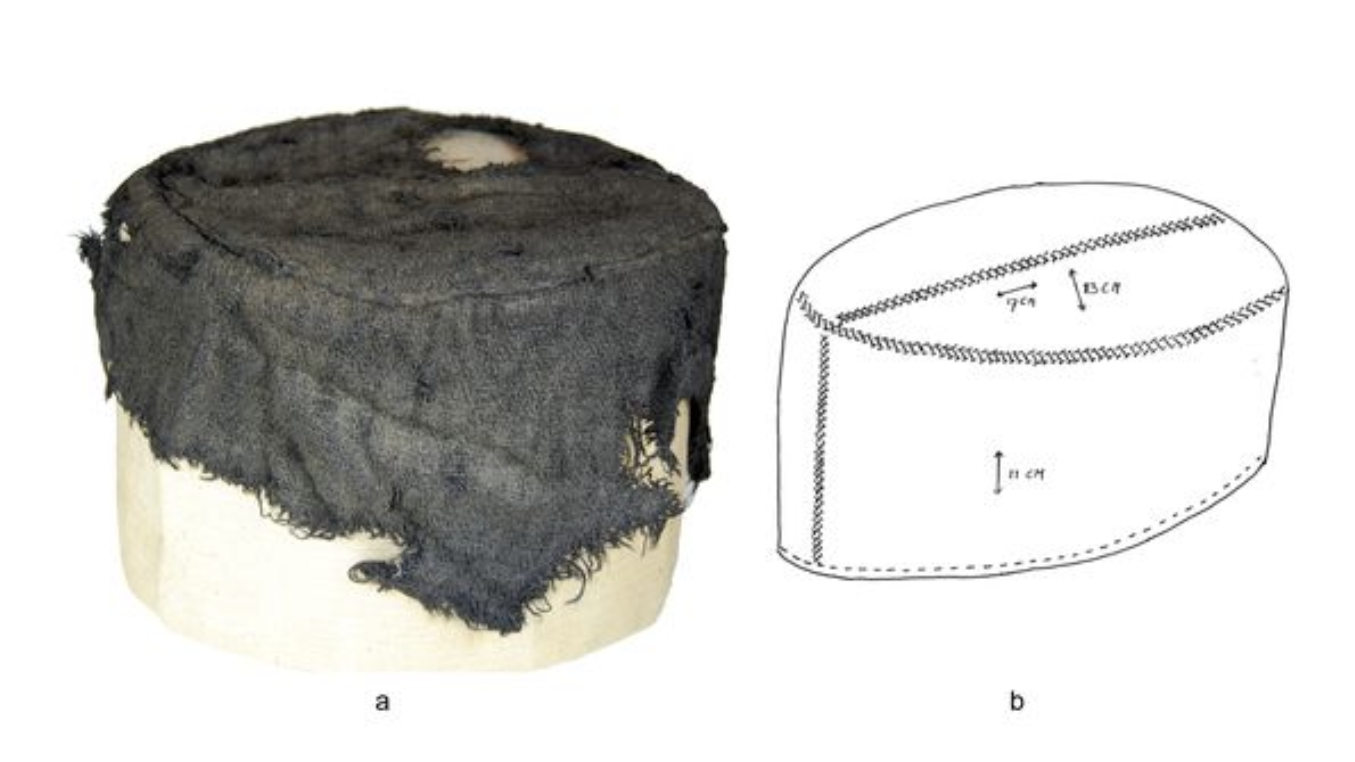

The mans hat

There is evidence pointing that a wealthy Scandinavian man during the Viking Age wore something on his head. Unfortunately, no textile was preserved next to the skull in grave A11, so I have to look for sources geographically further away.

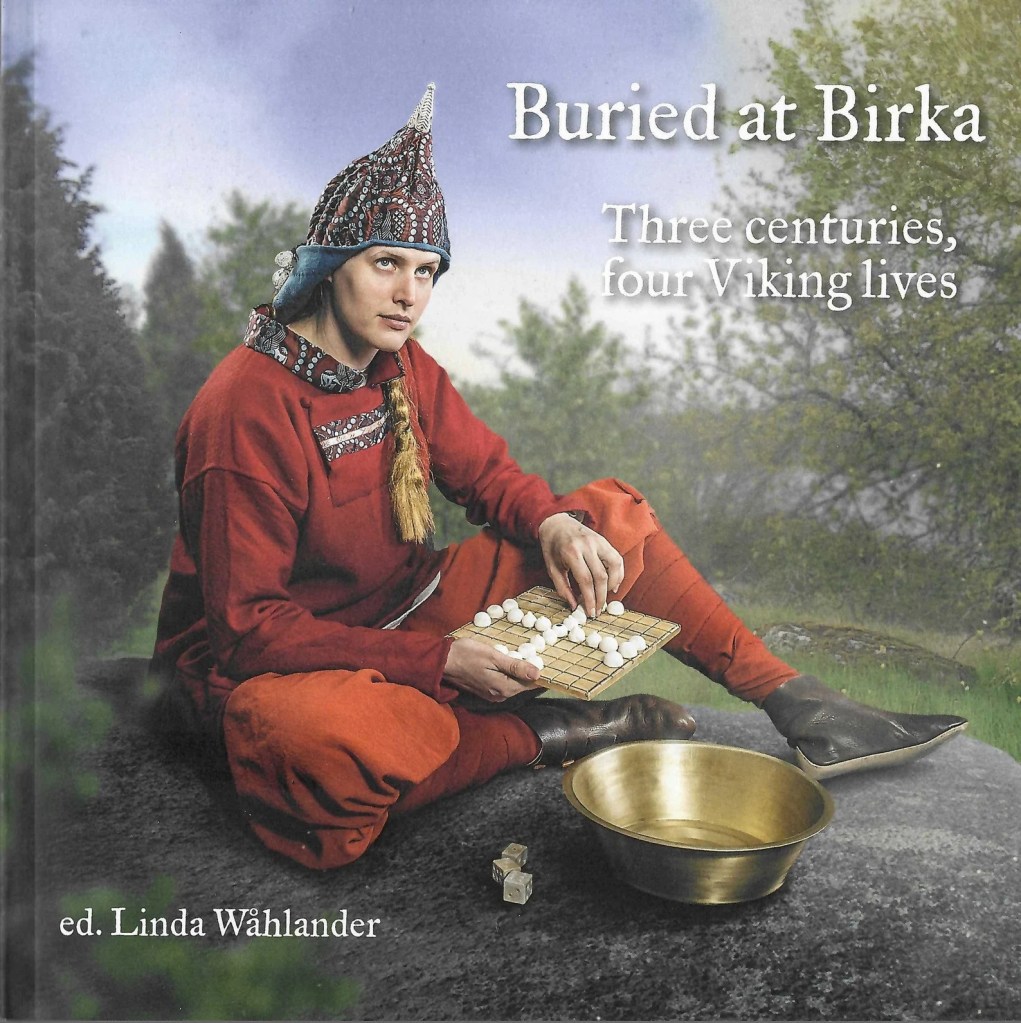

When looking at image stones and archaeological finds from the Scandinavian Viking Age, there seem to be a number of different forms of hats/caps for men during the period. Inga Hägg divides headgear for men buried at Birka into three categories.

Type A: An ostrich-shaped, pointed hat with influences from the East. In the Russian Moshchevaya Balka there is an archaeological, Viking Age find of a headgear that may belong to this category. Perhaps these headgears are also influenced by the Greek, pointed felthats called pileus.

Type B: A round-shaped hat sewn together from wedge-shaped pieces of fabric. A wedge-shaped hat like this, lined with fur, is also preserved from Moshchevaya Balka.

Type C: Some form of headband.

In addition to Inga Hägg’s three categories, there are also several archaeological finds of so-called “Pillbox hats” at several sites in northern Europe and Herjolfnäs in Greenland. However, the archaeological finds of Viking Age hats are fragmentary and the interpretations are many and varied.

I have decided to sew a “Pillbox hat” in my handwoven diamond twill. I base my hat primarily on an archaeological find from Leens in the Netherlands, an area that was more Danish during the Viking Age. Two similar hats have been found in Herjolfnäs in Greenland and in Hedeby in Denmark. The hat from Hedeby was probably sewn in a wool fabric that is made to look like fake fur. The two hats from Herjolfnäs were sewn in gray 2/2 twill and white, Greenlandic twill respectively. The hat from Leens was sewn in diamond twill which is similar to the qualities of diamond twill found in graves at Birka.

All hats had a similar design but the dates are scattered. The hats from Herjolfsnes in Greenland are dated to the 14th/15th century, but given that the island is so isolated, it is reasonable that fashion developed more slowly there. The hat from Leens is dated to the 11th century and made of three pieces of diamond twill sewn together. However, I have not found any information about color analysis. It also has decorative seams on the outside.

I was happy to read about how the diamond twill in the hat from Leens is described as stiff with several weaving flaws. It fits well with the diamond twill that I have woven myself. My fabric is very thread-tight in the warp which makes it stiff and of course the fabric contains a lot of weaving flaws because I am not a weaving professional.

On to the decorative wool seams which also serve as reinforcement. They are sewn directly onto the hat and reminds me of tablet weaving but are sewn with a needle instead. Time-consuming but fun. I chose to sew them on in a natural grey wool yarn to give a contrasting shade. Finally I plantdyed the hat blue with indigo.

The mans cloak

There are no textile remains in grave A11 that can be interpreted as a cloak, but cloaks occur in depictions of Viking Age male figures. Inga Hägg writes about about 10 archaeological textile fragments in graves at Birka that have been interpreted as cloaks and there is at least one find from Hedeby. The majority of these finds have a buckle or garment pin that holds the cloak together over one shoulder. If you look at how many cloak brooches have been found from the Viking Age, it is reasonable to assume that the man in grave A11 had a cloak as part of his clothes. A cloak is both practical protection against the weather and a garment that can show social status with strong colors. I have chosen to make a rectangular cloak in thick wool twill and plantdye it red with madder.

Viking Age bone/antler/wood pins are relatively common archaeological finds. They may have had several different uses, holding together cloaks/shawls or hairstyles. It is likely that bone and wooden pins were more common in the Viking Age than precious metal buckles, but many of these have decayed or been burned in connection with cremations.

The man in grave A11 had not been cremated, but much of the man’s bone material had decomposed, and it is possible that a wooden or bone coat pin had decomposed in the grave over the course of 1000 years. A coat brooch in iron, bronze or silver should have remained, however. So I have chosen to make a coat pin based on a model from an archaeological find in Sigtuna. The bone pin I have chosen is dated to 1050-1100, contemporary with grave A11, and was found in house A61 together with several similar bone pins. It is about 13 cm long and decorated with a checkered pattern. I made my coat pin from cow bone and it was unexpectedly easy and fun to carve out the shape and decoration. My pin is not an exact copy of the original, but similar enough to be a likely design in Uppland at this time period. To secure the cloak with the pin, I made a woolen cord on my replica of a Viking Age lucet from Sigtuna.

The mysterious wooden object with silver thread

At the foot of grave A11, the archaeologists found something that the report describes as “an unidentified object made of wood and twisted silver wire. From a small box or chest?” It also says that “the heavily decomposed remains of the object were found in an approximately 15 cm round imprint in the soil.” The report also includes a nice drawing of the object. I found this very exciting and made an appointment at the Historical Museum to examine and photograph the original.

Andersson, Gunnar (2003). Skälby i Sollentuna: bebyggelse och gravar under 2000 år.

When I looked at the original, I was fascinated by how thin the silver wire was and that it was most likely a repair. There are small holes drilled through the wood where the silver wire was threaded twice to sew a crack together.

My interpretation was that the wood is too thin and has the fibers in the wrong direction to be a box/small chest. In addition, there were small silver rivets in the wood with no obvious function. My first interpretation was that the object was what remained of a bentwood box with a wooden lid. The earliest known bentwood box date back to the Bronze Age and in Sweden there are traces of bentwood boxes from the Viking Age, not least among the Sami people.

I bought a hand-made bentwood box and cracked the lid to be able to recreate the repaired object. But to learn something, you have to be open to questioning your own interpretations and changing your mind, and I didn’t think the small rounding on one of the wooden fragments was right. Especially not in combination with the silver rivets. So I looked further for other references and found a very good collection article on the Project Forlog website about various European finds of wooden bowls repaired with twisted silver wire and decorated with small silver fittings along the edge. The silver fittings are of course riveted, which could be an explanation for the rivets in the object in grave A11. In addition, the rounding and fiber direction in the wood are better suited to a bowl than to a lid for a bentwood box. However, the report from grave A11 does not mention any remains of silver fittings.

I continued to look for more references in a Swedish context and found several examples of Viking Age wooden bowls decorated with riveted thin silver or bronze fittings around the edge and in some cases repaired with twisted silver wire.

Among other things, I found a Viking Age wooden bowl from Grötlingbo, Gotland. The grave was, just like grave A11, a Christian-coded skeletal grave and the bowl has riveted, double-folded silver fittings on the edge. It is also the same size as the object in grave A11, about 15 cm in diameter. Also in Birka there are archaeological finds of wooden bowls with riveted silver inlays on the edge.

So my new interpretation is that the mysterious object in grave A11 is a small silver-decorated wooden bowl with repaired cracks. I chose to decorate it with some silver fittings to test the theory of the silver rivets even though the silver fittings itself was not found in the grave. It seems more likely that someone went to the trouble of repairing a silver-decorated wooden bowl.

By chance I had a wooden bowl that was cracked and repairing the crack with silver wire worked surprisingly well. When I hammered in my handmade silver rivets to attach the silver fittings, I accidentally cracked the bowl in a new place but then I just had to get more silver wire and repair it the same way again. Experimental archaeology.

Since my knowledge of working with silver and wood is very limited, the result of the bowl is far from perfect. Only when I was finished did I discover that the bowl is probably made of a non-Scandinavian type of wood. And my handmade silver fittings are a bit crooked, but when you look at the original finds in my reference material, they are not always so skillfully executed either. I can’t possibly say that the object in grave A11 was a bowl, but that is my best interpretation based on the knowledge I have today.

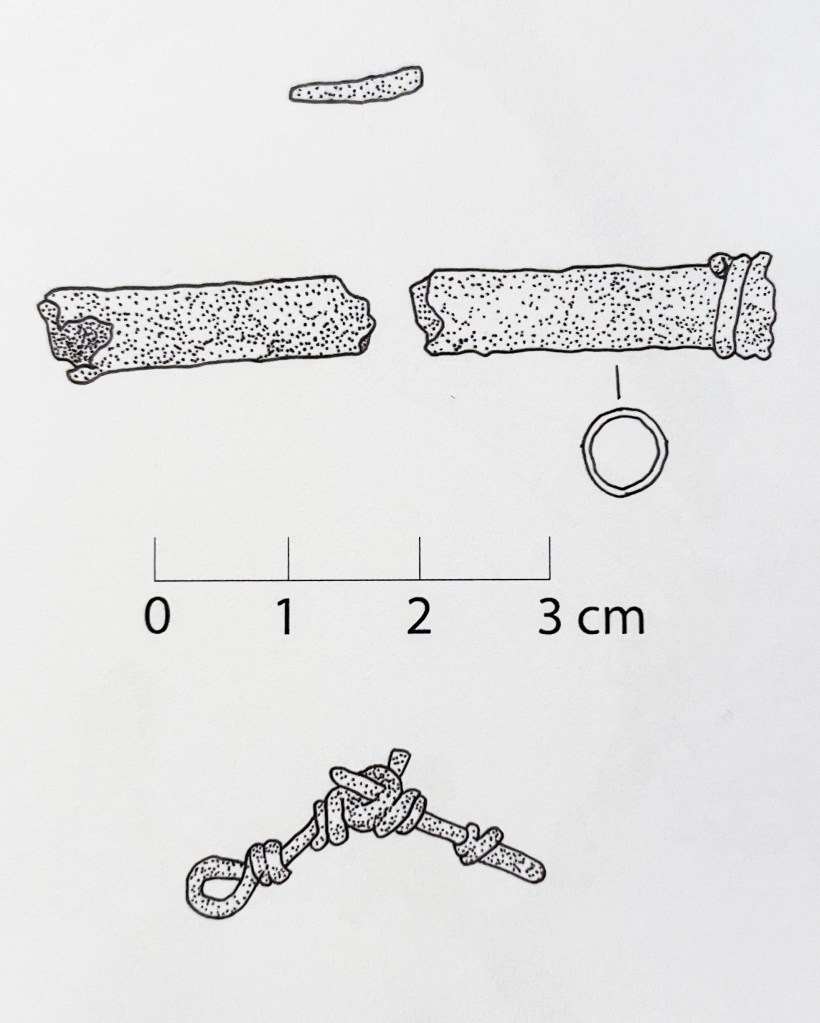

The women’s needle case, chain and ring brooch

In grave A28, a very small and simple bronze ring brooch was found, as well as a needle case together with fragments of a bronze chain/links. All grave finds were at the height of the woman’s chest/waist. Since the grave lacks buckle double brooches, my interpretation is that the ring brooch functioned as a tool buckle that was attached to the dress and carried the needle case via a chain. Similar solutions with a small ring brooch, chain and tool such as a needle case or key are common finds in women’s graves on Gotland during the Viking Age. When I read archaeological reports about other excavations in the area around Sollentuna, I discovered that a very similar needle case and chain were found in a smaller grave field just a few hundred meters from the one I am recreating. This one is also dated to the Viking Age.

I bought a replica of the needle case from Historical textiles and made the ring brooch, the chain links and the needle case ring from 1 mm thick bronze wire. It was tricky as the dimensions are so small but after a few tries I got an ok result. In a time when pockets had not yet been invented, this is a solution for having your needle case close at hand.

Andersson, Gunnar (2003). Skälby i Sollentuna: bebyggelse och gravar under 2000 år.

Andersson, Gunnar (2003). Skälby i Sollentuna: bebyggelse och gravar under 2000 år.

Dated 9th-12th century.

Photo: Hildebrand, Gabriel, Historiska museet/SHM (CC BY 4.0)

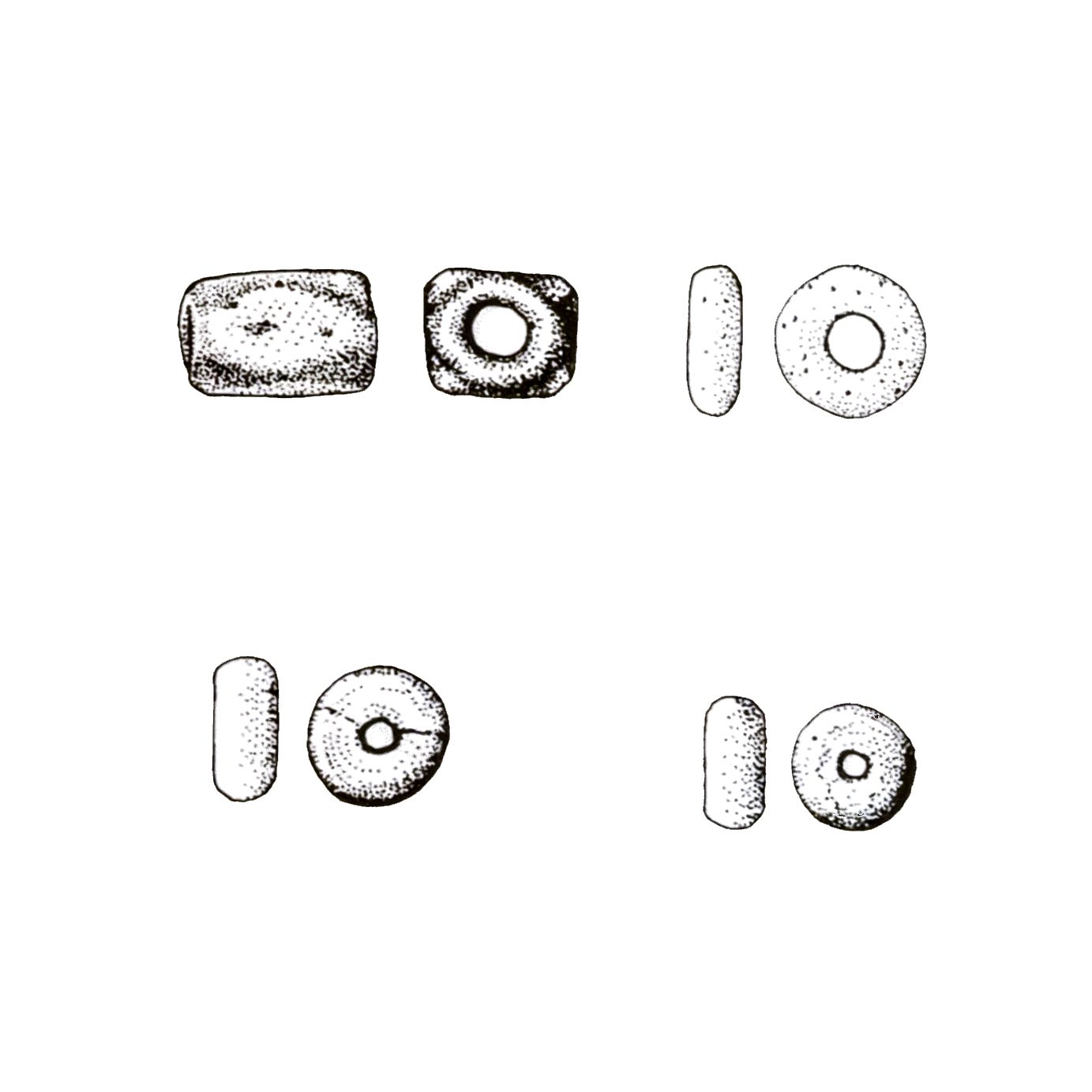

The women’s beads

In grave A28 there were two red opaque glass beads, one white opaque glass bead and one blue faceted glass bead. As the grave lacked dubble brooches and is dated to the late Viking Age when the fashion for dubble brooches and apron dresses was beginning to go out of style, my interpretation is that the beads were worn as a necklace. I chose to thread the beads onto a bronze wire of the same thickness as the bronze chain in the grave. The inspiration for that interpretation comes from a bead necklace in Birka, but it is a speculative interpretation on my part. The beads could just as easily have been worn on a textile or leather string. I bought the glass beads from Linda Wålander after examining and measuring the original beads at the Historical Museum.

.

Andersson, Gunnar (2003). Skälby i Sollentuna: bebyggelse och gravar under 2000 år.

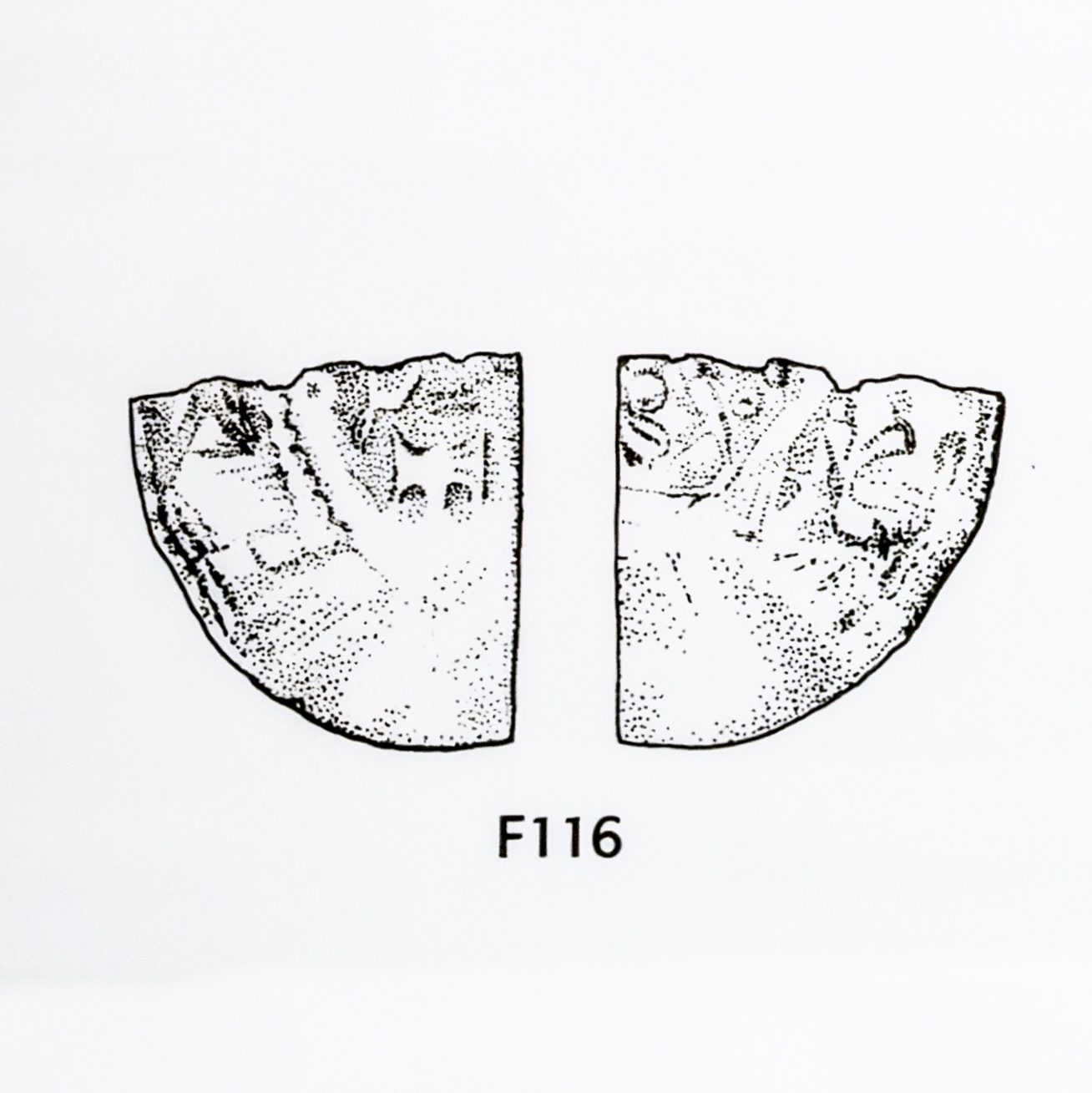

The women’s silver coin

Next to the woman’s right femur in grave A28 was a quarter silver coin minted for Henry IV, who was German king between 1056 and 1084. The coin helps with the dating of the grave but also indicates international trade contacts. Dividing silver coins into quarters was a common way for Scandinavians to handle coins during the Viking Age. It was the weight of silver that determined the value of the coin so dividing it into smaller pieces was a way to make it easier to weigh.

This coin proved difficult to find an exact coinstamp for so I stamped a blank silver coin of the right size as close to the coin’s pattern as I could by hand with a screwdriver and then broke it into four pieces. Not a perfect recreation but the right material and weight.

Andersson, Gunnar (2003). Skälby i Sollentuna: bebyggelse och gravar under 2000 år.

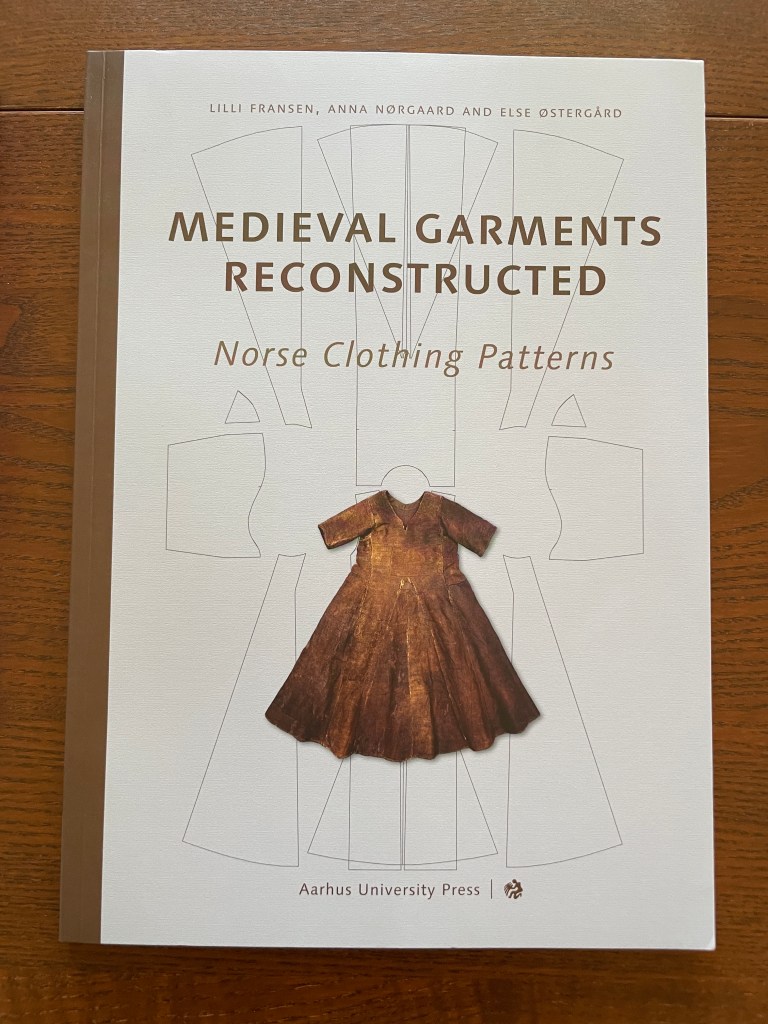

The women’s under tunic

Unfortunately, no textile fragments were found in grave A28 except for the silk threads, but I chose to sew an under tunic in undyed linen based on Inga Hägg’s interpretations of textile fragments in graves at Birka and Hedeby. The under tunic is hand-sewn with waxed linen thread in rectangular pieces with wedges in the sides and a slit at the neck. I chose to sew it calf-length so that the linen does not absorb moisture and dirt from the ground. Having a linen under tunic closest to the body is practical as it is easy to wash. I sewed it wide enough to be used even during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

The women’s dress

The thing that took the longest time in this entire project was weaving the fabric for the woman’s dress. Since there were no fabric fragments in the grave, I chose to weave a woolen fabric in diamond twill based on the fabric fragments found in rich Viking Age graves at Birka. With the fantastic help of Maria Neijman and Amica Sundström, I wove a 70 cm wide woolen fabric with single-ply undyed yarn.

Like many fabrics from the Viking Age, it is dense in the warp, about 22 threads per cm, and looser in the weft, about 10 threads per cm. It was a challenge in patience and calculation for me to weave this pattern, but it was worth the effort because the fabric turned out very beautiful.

Photo: Ola Myrin, Historiska museet (CC BY 4.0)

When the fabric was finished, I handsew a long-sleeved, floor-length dress with a round neckline, in rectangular pieces with four gussets. Initially, I had planned to only have gussets on the sides, but since I was limited by the width of the fabric of 70 cm and wanted to avoid more than a handful of fabricwaste, I added gussets at the front and back for greater mobility. The fabric was a challenge to sew in as it is stiff and thread-tight but at the same time easily scratches at the edges. Therefore, I chose to sew small reinforcements at the top of the gussets. Such reinforcements also appear on some of the tunics from Herjolfnäs in Greenland. (Thanks to the gussets, the dress can be worn well into pregnancy, which was probably a practical requirement during the Iron Age.)

After sewing, I first plantdyed the tunic yellow with reseda and then a second dye with indigo. The result was a mint green shade. Not exactly the color I had in mind, but the fun thing about plantdyeing is that the shades don’t always turn out as you’d expect. Since green requires two dyeings, it’s still a fitting color for someone from the upper class of the Viking Age.

Many thanks to Cecilia Smedberg for a really cozy plantdyeing day.

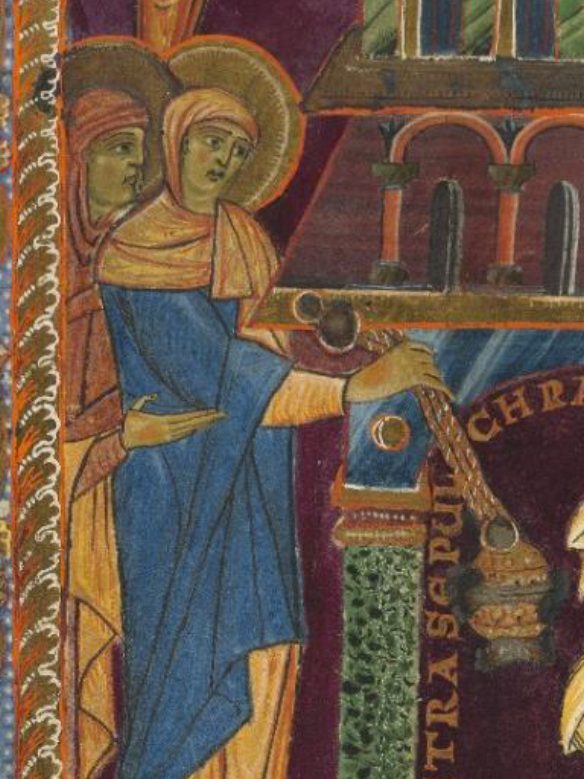

Silk threads were found in connection with the knife in the grave and if you look at the knife’s position in relation to the skeleton, my interpretation is that the woman in the grave wore silk in her dress at the height of the neckline of the dress. This also fits well with findings of silk decorations on clothes from Birka. It is known from several grave finds from the Scandinavian Viking Age that the silk decorations consisted of thin strips of imported, pattern-woven silk, usually no more than 1 cm wide.

I chose to decorate the neckline and sleeve ends of the dress with 1 cm wide strips of reconstructed silk from the Oseberg grave in Norway. The silk was probably imported from Persia and even though the Oseberg find is from the 9th century, it is likely similar with Byzantine silk produced in the East and imported to Uppland the 11th century.

The women’s shawls

Scandinavian sources about what women in the Viking Age wore on their heads are few. Female figures on jewelry are often depicted with long hair tied up in a knot. However, these may be depictions of goddesses or have another symbolic meaning, so they are not a credible source for what Viking Age women actually looked like. The woman in grave A28 also lived in the 11th century when Christian fashion probably influenced people in Uppland.

I have chosen to sew and plantdye two rectangular woolen shawls for the woman in grave A28 even though the grave lacks preserved woolen textile fragments. I base this interpretation on several images and archaeological finds from other graves in Viking Age Scandinavia. However, it can be difficult to know which textile fragments in a grave belonged to the clothing or to wraps/blankets/pillows. Inga Hägg writes this about female graves at Birka:

“Wool that lay under the brooches and the body’s decomposition remains and thus originates from the back of the garment, is found in 14 of the graves. 11 times, i.e. in 9 of the 14 graves, the same kind of wool is also found on the brooches shells. They must then originate from a garment that lay around the body outside the apron dress, probably a shawl.” Hägg 1974, p. 84

The qualities that are most common in the archaeological grave material from Birka are diamond twill and 2/2 twill, but plain-weave wool is also present and often these are thin, fine qualities.

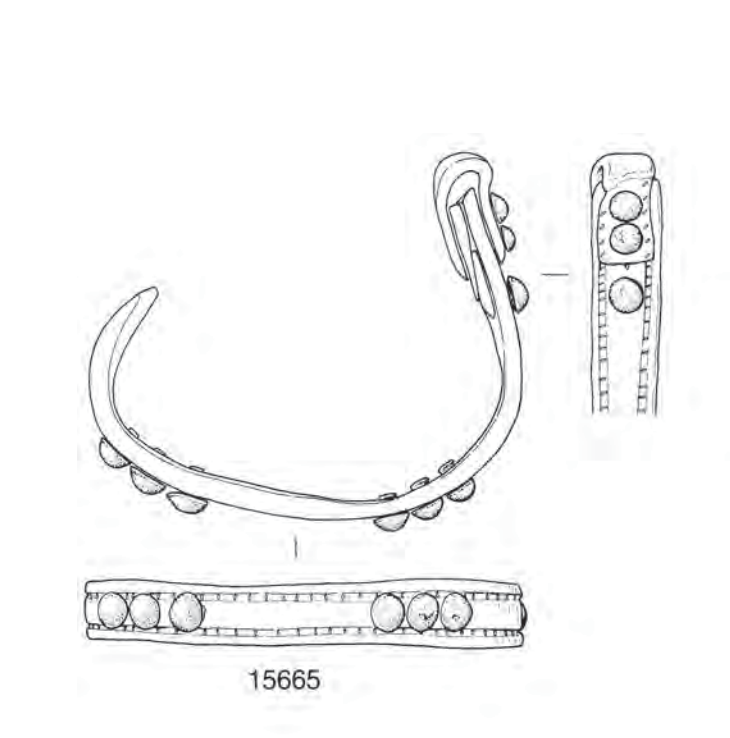

I have chosen a wool fabric in 2/2 twill that I wove myself for the larger shawl. The fabric has about 22 threads per centimeter in the warp, in accordance with the majority of textile fragments from graves in Birka. I wove it with natural gray wool yarn and plantdyed it with madder. When weaving on a standing warp-weight loom, it is not practical to weave wider than about 70 cm. (I did weave on a modern loom, however) So my shawl is a 74 by 220 cm rectangle.

I base the rectangular shape and size on various Viking Age depictions such as the “Valkyrie pendant” from Botkyrka, a pendant from Tuna in Uppland, the Oseberg tapestry from Norway, and others. There are also many fine depictions of women with shawls on all the “Gold foil figure” that have been excavated. However, these are dated to the Vendel period or early Viking Age. All of these archaeological finds depict women with a rectangular shawl that either hangs straight down or is folded double like a triangle over the shoulders.

I have chosen to have the shawl finished on both sides with fringes that I twisted from the warp threads. Fringes are a practical way of fixating the fabric without hemming the edges and there are both archaeological finds and depictions that indicate shawls with fringes. One example is the very well-preserved wool shawl from Huldremosse in Denmark. However, it is dated to the Roman Iron Age. In Denmark there is also a Viking Age find of a small pendant with a female figure that has been interpreted as having fringes on the shawl. (Mannering 2017, p. 114) There are also several shawl fragments from graves in Finland, dated to the Finnish Late Iron Age (800-1055/1300 AD). These shawls were decorated with spirals of copper alloy that often preserved the shawls’ fringed edges. (Hägg 1971, pp. 141-142).

Unfortunately, no brooch or pin was found in grave A28 that seems suitable as a shawl brooch/pin. (The small ring brooch is too small and flimsy.) But you don’t have to have a brooch/pin to drape a shawl over your shoulders, so I have chosen not to.

Photo: Ola Myrin, Historiska museet

CC BY (4.0.)

Photo: Ola Myrin, Historiska museet

CC BY (4.0.)

Photo: Eirik I. Johnsen, Kulturhistorisk museum CC BY

Photo: Cheyenne Olander/Björn Falkevik

CC BY National museum of Denmark

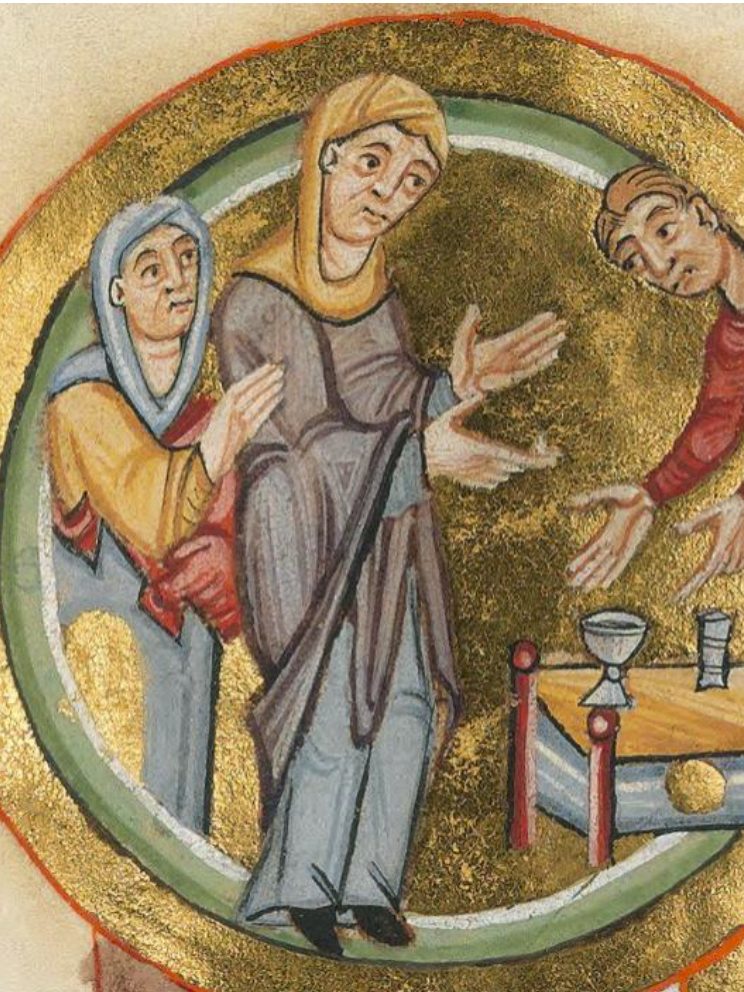

I have also chosen to sew a smaller shawl/veil in a thin natural-colored wool twill that I have dyed blue in a strong dyebath with vejde. You can see in many manuscript images from northern Europe around the 11th century that women have a shawl in bright colors around their heads. These are images in a very Christian context, but since the woman in grave A28 has a Christian skeleton burial and lived in the 11th century, I chose to sew a long rectangular head shawl. After all, this is a time of change between older and new traditions, clothing fashion and religion.

(date ca. 1000-1007)

(date ca. 1020-1025)

(date ca. 1000-1007)

The women’s knee-hose

To keep my feet warm, I have chosen to hand-sewn a pair of knee-high hose in undyed, white wool, 2/2 twill. I have then dyed them light brown with walnut leaves because it is a more practical color for hose than white. The sources for Viking Age women’s legwear are largely non-existent, so I have chosen to be inspired by the hose from Thorsberg and Hedeby, as well as looking at many medieval manuscripts from Europe. In other words, I have very little to back up these garments except that they are practical and common among women in the Middle Ages.

New York Pierpont Morgan Library, MS G.24.

Date ca 1350

Source: The Morgan Library

Source: Fitzwilliam Museum

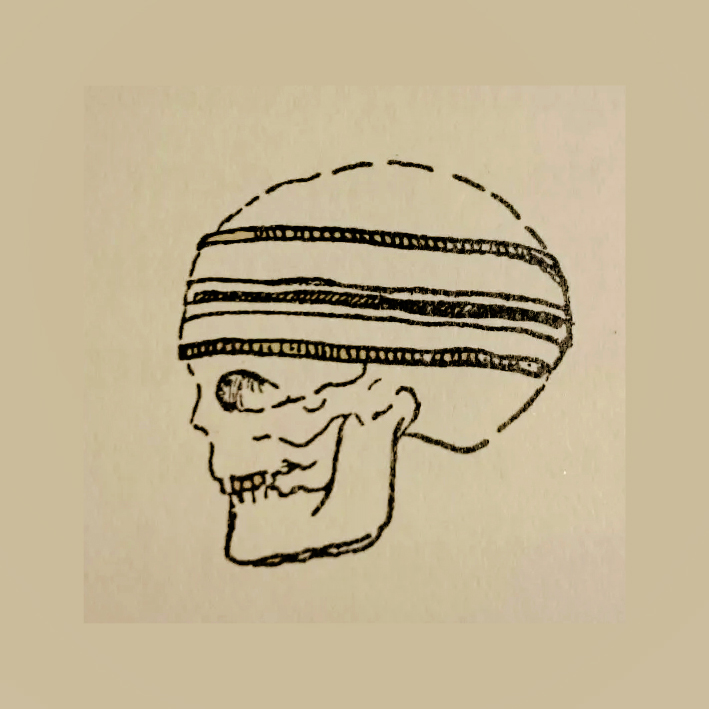

The women’s shoes

No fragments of shoes were found in grave A28 and as leather decays quickly it is extremely unusual to find preserved remains of shoes in graves from the Iron Age. However, I believe that people were buried with shoes because they were given so many other grave goods and fancy clothes in the grave. And even though this is a Christian-coded grave, the tradition of personal grave goods still lives on in Uppland during the 11th century.

I wanted to recreate a shoe model that was found as close in time and geography as possible and after talking to experts Sofia Berg and Henrik Summanen I fell in love with an archaeological find from Sigtuna. It is a rather strange high-heeled strap shoe. As far as I know, it has never been recreated before and it fits well both geographically and temporally with grave A28. To my great delight Sofia agreed to sew me a pair. The shoes are turned-sewn on a last with boar bristles. It turned out that the strange high heel provides practical protection against chafing on the achilles tendon from the straps. These shoes are an interpretation of the find in Sigtuna and fit me perfectly. Many thanks Sofia Berg.

Summary and lessons learned

Would the people in graves A11 and A28 in Sollentuna recognize themselves in what I created? Maybe, but so much is based on my interpretations based on archaeological finds from geographically and temporally different places that there is certainly a lot that they would not recognize. But that is also the charm with reenactment/experimental archaeology, that the more I learn, the more I realize how little I know. And there is always more to learn and try.This is not a truth about of what “vikings” looked like. It is just my interpretations and guesses based on small fragments in two graves in Sollentuna.

I will content myself with summarizing the project like this: It was fun. I learned a lot. It took a long time.

Big thanks to

To the Swedish National Heritage Board and the Vitterhetsakademin library for the opportunity to take part of the archaeological report.

To Gunnar Andersson and colleagues for a well-written and detailed archaeological report.

To the Historical Museum in Stockholm for their fantastic database of find images licensed under Creative Commons and the opportunity to look at the objects in person. Sharing is caring.

To my friend Maria Neijman, (Historical textiles) for encouragement, weaving help, plant dyeing tricks and wonderfully geeky conversations.

To my missing friend Amica Sundström, (Former Chief Antiquarian for the textile collection at the Historical Museum and Historical textiles) for all the help and encouragement with the weaving and geeky conversations.

To Cecilia Smedberg for a really cozy plant dyeing day.

To Peter Johnsson for wonderful geek knowledge and conversations about Viking Age knives.

To Thomas Cederroth for help with forging the knives at Skeppsholmen’s forge.

To @MagyarTarsoly for skillful casting of the metal details for the belt.

To Faravid for knowledge about strap-sewn belts and the craftsmanship of the knife sheaths.

To Sofia Berg and Henrik Summanen for super interesting discussions about Viking Age shoes and the craftsmanship of the Sigtuna shoes.

To Torvald’s Leather Workshop for the Hedebyskorna.

To Linda Whålander for the glass beads and interesting blogging all these years.

To Project Forlog for excellent compilation of sources and archaeological knowledge.

To my former colleagues at The Viking Museum for encouragement and talks.

To my dear partner Lars-Erik for support and patience with my craftsmanship chaos and for standing model/photographer/moral support even when I blew the fuses in the apartment.

To all friends and acquaintances in the reenactment and archaeology community who constantly share and inspire.

All photos above without source reference are photo: Cheyenne Olander

Some of my sources